Since 2004 the artist Ryan Gander has performed the Loose Association lectures i. These events seem to have pre-‐empted a rise in artists using the performance lecture as medium to present a constellation of works and ideas that are sympathetic to things that might be unresolved or unfinished. The Loose Association lectures have become a touring work that is iteratively re-‐constituted each time the work is presented. So far there have been around 15 versions. The lectures are sequential in that they move between subject matter paragraph to paragraph and image to image. Photographs, moving image and stories all accumulate into an hour-‐long performance that deliberately plays upon the conventions of the lecture as a standardised academic format for the distribution of knowledge ii.

I wanted to begin in the same way that Gander did, by presenting ‘Desire-‐Lines’ within my research. The research inhabits spaces between architectural and written practices, so I’m attempting to present desire lines that might forge a relationship not only between the fragments of artworks but to consider the demarcation of desire lines as something written. How can both the literary and the architectural operate as spatial strategies; minor architectures as minor literatures that develop from a similar structural position?iii Canclini uses the term imaginarioiv as a counter to scenario, when thinking about spaces contingently, that is to say to consider alternate and provisional realities that in turn can be used as a critical position for architectural forms. The imaginario concept is connected to the social imaginary and how space is experienced, in both utopic and traumatic ways: ’a fold of space and temporal gap between the now and the past and hence the now and the future'.v

In the film Die Architektenvi (dir. Peter Kehane), a group of idealistic young architects are commissioned to produce a cultural centre for a Housing Estate in Marzahn, Berlin by the East German building committee. In one scene mid-‐way through the film, the assembled team is gathered around a drawing board talking through possibilities for pedestrian movement between the centre and a nearby railway station. The proposed pathway is endorsed by one architect as ‘affirming natural pathways’, whilst another critiques its lack of imagination and freedom. This small sequence encapsulates the conflict between architectural practices in the German Democratic Republic, whereby established fixed building matrices (such as the Plattenbausvii) are preferred to a ‘counter-‐hegemonic space’viii. In a later scene, one senior architect points out the representational power of architecture in the GDR:

‘Building is political. We project power. Each building reflects status, like it or not. Prosperity or austerity. Dreams or despair.’

You don’t really think about desire lines so much in cities like London or Maastricht because these tend to be much less reliant on the grid as a method of urban planning. I became much more aware of this when I spent some time in Los Angeles where the grid is not only spatial divide but also a conceptual one too; at the time I wroteix:

Hoover Street running southwards from Hollywood

to the University of Southern California, marks a

threshold where the 90-‐degree grid system of West

Los Angeles meets the 45-‐degree clustered streets

of Downtown; manifesting the economic and social

push-‐pull that shaped so much of the city since

the 1920s. The high-‐modernity of Piet Mondrian’s

perpendicular crushed next to Theo Doesburg’s

diagonals. This collision of abstractions also manifests in

Bas Jan Ader’s film Broken Fall (Geometric)x recorded

in front of Mondrian’s lighthouse at Westkapelle. The

artist stands upright, swaying in increasing motion

with the breeze until a lean becomes a fall and Ader

collapses across a propped wooden work-‐bench.

i In 2007 three of Gander’s texts were compiled into a publication Loose Association and Other Lectures published by Onestar Press and offered as a free PDF download. Versions 1.1 , 2.1 and 2.4 were included, the numbered iterations indicate the direct continuation of a loose association lecture to the next. The publication presents a tension between text that masquerades as a transcript and the presentation of the live form as a graphic event, being both a pre and post produced work.

ii Renard, Emilie (2007) tr. Malovany-‐Chevallier ‘This Way Ryan’ in Loose Association and Other Lectures Onestar press p.12

Desire lines in LA seem profound and tied to the economic desires of America. I am always staggered to think just how planned the United States is, dating back to the land ordinance of 1785, which stimulated the settling and selling of land in the New World. I think that’s pretty radical bearing in mind it was a pre-‐taxation initiative that successfully encouraged settlers to move further westwards under a pioneering guise rather than the profit-‐making federal enterprise, which it was. Much later on, the Homestead Act of 1862 granted all US citizens a piece of public land. Apparently 10% of the landmass of the United States was given away free to land-‐owners. Homesteaders as they were called, were required to live on the land and build themselves a home to farm on for a minimum of five years. No restrictions were placed on who could apply, encouraging immigration and industry into the developing country. It was also around this time that the Central Pacific Railroad Company began laying infrastructure to connect the more industrial developed East to the emerging potential of the West. Massive subsidies were granted to the CPRC as the US government realised the immense economic potential of land, mineral and materials that lay to the West.xi Construction began from the East in Council Bluffs, Iowa and Sacramento, California in the West. The two advancing workforces met at Promontory Summit in Utah 1869. A ceremonial golden spike; ‘The Last Spike’ was hammered into place completing the uninterrupted 1900 mile track.

Moving East-‐West and then West-‐East has been the unifying factor between my research undertaken in the former East Germany and the current West of the United States. I’ve been thinking a lot about how back and forth movements contribute to research, and how the creation of fictional vantage points allow for objects of research to be re-‐considered. For instance an imagined scenario in Peter Schneider’s novel Wall Jumperxii. Here two stories describe East-‐West & West-‐East Berlin wall-‐jumpers from perspectives either side of the wall, with each tale told by a separate character and both rendered through fiction. The final story describes a contingent scenario whereby the 2 sets of wall jumpers encounter one another. I’m not sure if this contingent demand operates as a provisional space, and if it does, what then takes place in that space. Here's an image of a scrubland on the Eastern side of the wall set behind the crossroads of Jerusalemer and Schuetzen-‐Straße. On the site, a memorial to murdered border guards was erected by the GDR government from 1973.

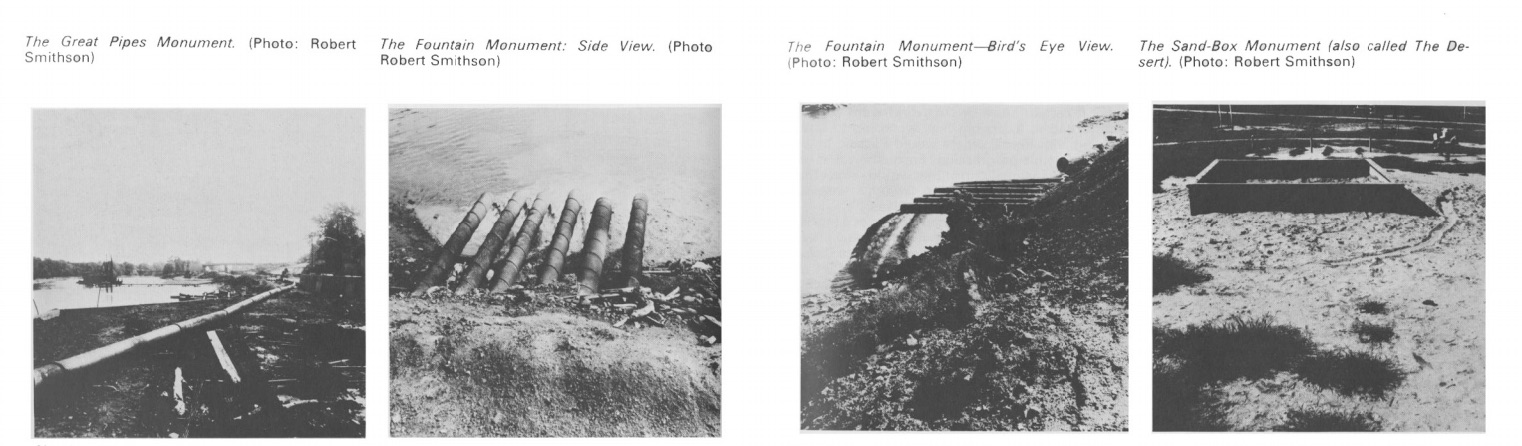

In the 1967 December issue of Artforum, Robert Smithson’s essay ‘A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’ was published. The essay is written from Smithson’s perspective as he departs Port Authority in New York to visit the small post-‐industrial town of Passaic. Each industrial structure is elevated to the dignity of a monument, its image captured in perpetuity by Smithson’s Instamatic 400.

“From the banks of Passaic I watched the bridge rotate on a central axis in order to allow an inert rectangular shape to pass with its unknown cargo. The Passaic (West) end of the bridge rotated south, while the Rutherford (East) end of the bridge rotated north; such rotations suggested the limited movements of an outmoded world. “North” and “South” hung over the static river in a bi-‐polar manner. One could refer to this bridge as the “Monument of Dislocated Directions.”xiii

Later in his journey, Smithson comes across a sand-‐pit in a children’s play park –his final monument ‘a map of infinite disintegration and forgetfulness’. The sand-‐pit is used to illustrate the concept of entropy, inviting us to imagine the box divided equally between white and black sand. A child runs clockwise hundreds of times until the two coloured sands are mixed to become grey. Then he is asked to run anti-‐clockwise, but instead of a reversal and separation of the 2 sands a greater degree of greyness and entropy is the result. I’m not entirely sure but I think that this also has something to do with the ‘3rd provisional space of Schneider’s Wall Jumper and the meeting of the 2 sets of CPRC workers at Promontory Summit. Furthermore these moments can be considered points of convergence, a kind of proposed desire line that draws objects of research together.

In the 1970s substantial political changes took place in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which had consequences for East German cultural identity. The heritage preservation lawxiv (1975) attached particular importance to historical monuments, which contributed to an image of the GDR as its own nation. This law used party testimonies in a process of designating recent buildings under new preservation orders. As a result younger technical monuments like the Berlin TV Tower (1969) were on the register alongside architecture from the immediate post-‐war period. Buildings from the 1970s were registered a few years after their completion. This practice culminated in the publication ‘Monuments of GDR History’ in the 1980s – a project which remained unfinished. As part of her research, Simone Bogner located the manuscript of this book in an archive, that was meant to be published in 1989, but never was, due to the events that year. The book presents 360 objects, which are connected to GDR history. This is a site we photographed as part of the project. It is a location we visited during a summer expedition around the vicinity of Leipzig. I took the picture just as the sun was going down on the late summer’s evening. The buildings you can see here are actually part of a still-‐functioning Children’s holiday camp Werner Seelenbinder in Güntersberger. Here’s part of the camp from 1964.

This particular location is marked on our manuscript as ‘Land where Kurt Dillge was murdered in 1953’. Kurt Dillge, a SED district leader was instructed to investigate suspicious industrial practices at the local sawmill (sounding like a plot from Twin Peaksxv). Whilst undertaking his investigations, Dillge was murdered in the forest at the site of the holiday camp. This was one of the more difficult monuments to photograph, as there isn’t really an object of focus or a point of remembrance. It presented the problem of an innocent site overlaid with the trauma of an unresolved murder.

In cinema the ‘MacGuffin’xx refers to an object or a device that holds no narrative importance or value and is only used as a trigger point for the plot – functioning as a dumb object. One notable example would be the Maltese Falcon from the film of the same name. Towards the end of the 1970s, LA artist Ed Ruscha created the work Rocky IIxxi. The work consisted of a fake resin rock fabricated by the artist and installed somewhere in the vastness of the Mojave Desert. Its location remains a mystery, with Ruscha unwilling to divulge its whereabouts. In 2015 Pierre Bismuth produced the film ‘Where is Rocky II?’xxii documenting the almost futile attempt to locate the fake rock in the expanse of the desert. Bismuth took his task very seriously by employing private investigators and interviewing associates of Ruscha to determine the rock’s existence.

In the chaotic aftermath of the Berlin Wall’s collapse in late 1989, pieces of the wall were broken off and sold as souvenirs to tourists and historical enthusiasts around the world. What is less publicized however, is how the GDR government commodified the wall in one of its final sovereign acts. East German foreign-‐trade company Limex-‐Bau were awarded a contract to dismantle and market fragments of the Berlin Wall to international buyers.xxiii During the 1980s Limex-‐Bau was part of a commercial contract between the GDR and Ghana that traded construction services for cocoa beans. Official pieces of the Berlin Wall were issued with an accompanying certificate of authenticity produced by Limex-‐Bau. 360 segments were distributed across the globe, with profits eventually going to historical preservation funds. One such section can be found on 5900 Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles.

The more I think about the use of desire lines in the work the more I realise they become the material between the objects of Gander’s lecture. I’ve been thinking about desire-‐lines as another way of armaturing a method that allows for difference between minor and major moments of an artwork or a project (or both). A desire line is an urban planning phenomenon where usually pedestrians ignore planned pavements or walkways between buildings and create alternative routes. These paths are usually the most direct or quickest, but walkers may also favour a route that is more scenic or safe. It is possible that more than one desire line can exist at any given time. But eventually there must be a moment where the repeatedly trodden steps of a single desire line supersedes all others. The improvised line becomes the de-‐facto route as more and more people reject the designed pathway.

The essay Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben (tr. On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life) by Friedrich Nietzsche (1874) became an important text for the research project ‘The Nietzsche Memorial Hall’ (Knight & Bogner, 2012) in Weimar, Germany. This was the first instance in my work where I examined the possible reflexivity between architecture and text. The Nietzsche Memorial Hall had been subjected to re-‐appropriation and instrumentalisation through ideological forces of the twentieth century: beginning with the National Socialists who commissioned the building in 1937, continuing through the German Democratic Republic and ending in its current state of abandonment. On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life describes the worth and worthlessness of historical knowledge and problematic subjectivities surrounding historicity. This is pivoted through Nietzsche’s identification of three kinds of Historian; the monumental, the antiquarian and the critical:

.

‘If a man who wants to create greatness uses the past,

then he will empower himself through monumental

history. On the other hand, the man he wishes to

emphasise the customary and traditionally valued

cultivates the past as an antiquarian historian. Only

the man whose breast is oppressed by a present need

and who wants to cast off his load at any price has a

need for critical history, that is, history which sits in

judgement and passes judgement.’xxiv

The use of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s work for the purposes of National Socialist ideology is often attributed to his sister Elisabeth-‐Förster. This is most evident in the expansion of Nietzsche’s final work The Will to Power, where his own notes were revised and re-‐written for publishing. xxvCopyright on Friedrich Nietzsche’s writings were held by his sister until the end of 1930, leading to the re-‐publishing of Nietzsche’s texts by private publishing houses, the most notable being Reclam in Leipzig. This also allowed for newly published compendiums to emphasise different elements of Nietzsche’s oeuvre. The philosopher Alfred Baeumler, edited much of Nietzsche’s published outputs during the 1930s under the influence of the Nazi Party. The 1924 edition is the first time the essay had been published separately. The changing frequency of publishing throughout the twentieth century indicates how Nietzsche’s legacy undergoes constant revision and politicisation. Proportionally the majority of copies were published in the pre-‐war period; particularly through the nineteen-‐thirties and early forties. Publishing slowed down considerably in the post-‐war years only returning in frequency in the latter part of the twentieth/early twenty-‐first century.xxvi

The East German response to the European Preservation Lawxxviii was the creation of the ‘Cultural League of the GDR’, that also emphasised history at a localised level, through proletariat buildings and objects. Part of this community-‐focussed initiative resulted in the construction of ‘antifascist tradition cabinets’; a repository of sorts, housed in buildings scattered around East German cities.xxix These cabinets held the artifacts and possessions of concentration camp victims. Tours were set-‐up for GDR citizens to experience these objects as a constructed spectacle of history. The cabinets were designed to elicit anti-‐fascist sentiment and to enforce the GDR as an ideological presence.

In 2003 Cabinet Magazinexxx, purchased an unseen half-‐acre plot of land located near Deming, New Mexico for $375. Inside Block 4, Lot 8 is Matthew Passmore’s Cabinetlandia; a set of office cabinet drawers installed into a dirt-‐bunker. The Cabinet National Library holds every copy of the magazine and is archived for desert visitors. Cabinetlandia recommends a good pair of hiking boots to protect against snake-‐bites and scorpion stings.

The artist Andrea Zittel, after having spent 10 years in New York decided to re-‐locate to the quietness of the Mojave Desert in 2000. Using the Small Tract Act of 1938xxxi Zittel purchased a small land holding of 5 acres along with a homestead cabin. The cabin had been previously used as a holiday home for retirees. Through this base Zittel expanded the site to include neighbouring plots of land. The now-‐50 acre plot exists as a Test Sitexxxii for ways of living in remote or hostile conditions. On the northerly frontier are a series of ‘Wagons – small habitable living pods designed by Zittel that host visitors wanting to work and explore the test sites.

Interview with Lucy Lippard

Lippard was one of the first examples I encountered where the boundaries between work and writing became fully collapsed. She lives in a small modified Adobe home cramped with books and artworks, her situation felt like the authentic intellectual life. She was gracious to invite us on a walk we strolled through the sleepy streets in Galisteo where dogs and their owners paused to greet Lucy. She spoke mostly of her life in Galisteo stay how and I’m close community had established itself during the 1950s it was a place she has visited during her previous life in New York in some respects her story of self-imposed exile into rural New Mexico was fairly typical and her position and working life afforded a sense of remoteness. It was hard for me to assemble questions there was nothing I wanted to know - the walk around the neighbourhood was a form of knowledge. It was a kind of paralysis that the landscape imposed upon me, a will of silence, a distrust of voices and language, of naming and identity and ignorance and a Knowledge. I could only be alone in this environment the pathetic gesture of the artwork lacking what then we place emphasis on collecting, collaboration and organisation. To do anything other than withdraw feels profane.